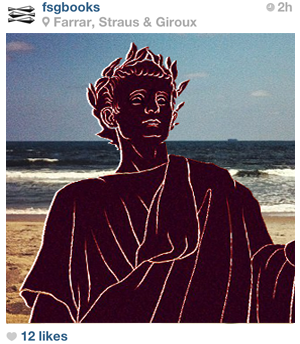

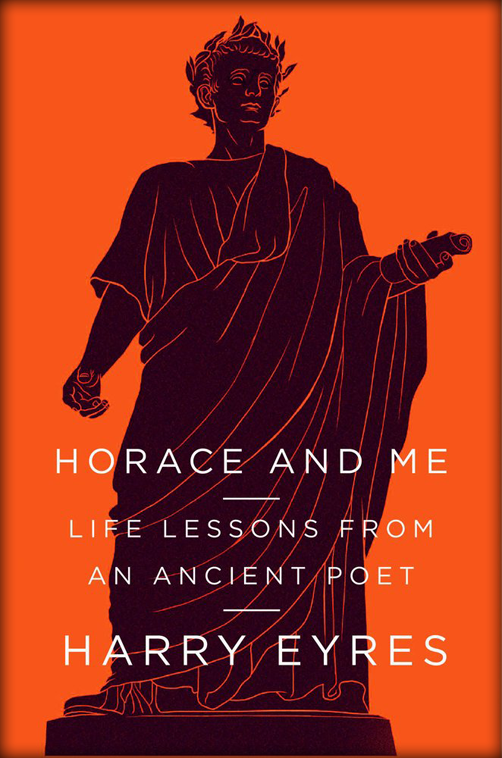

A wise and witty revival of the Roman poet who taught us how to carpe diem

What is the value of the durable at a time when the new is paramount?

How do we fill the void created by the excesses of a superficial society?

What resources can we muster when confronted by the inevitability of death?

For the poet and critic Harry Eyres, we can begin to answer these questions by turning to an unexpected source: the Roman poet Horace, discredited at the beginning of the twentieth century as the "smug representative of imperialism," now best remembered-if remembered-for the pithy directive "Carpe diem."

In Horace and Me: Life Lessons from an Ancient Poet , Eyres reexamines Horace's life, legacy, and verse.

With a light, lyrical touch (deployed in new, fresh versions of some of Horace's most famous odes) and a keen critical eye, Eyres reveals a lively, relevant Horace, whose society-Rome at the dawn of the empire-is much more similar to our own than we might want to believe.

Eyres's study is not only intriguing-he re-translates Horace's most famous phrase as " taste the day"-but enlivening.

Through Horace, Eyres meditates on how to live well, mounts a convincing case for the importance of poetry, and relates a moving tale of personal discovery. By the end of this remarkable journey, the reader too will believe in the power of carpe diem.

Horace's "lovely words that go on shining with their modest glow, like a warm and inextinguishable candle in the darkness."

“Horace’s time and ours are linked by a curious sense of hollowness at the heart of unparalleled prosperity." -Horace and Me,

Harry Eyres has become one of the most eloquent representatives of the worldwide Slow Movement. Having worked for leading newspapers and magazines as a wine writer, theater critic, and poetry editor, he created the international Slow Lane column in the Financial Times in 2004.

Slow Lane encourages and facilitates thoughtful enjoyment of the profound, and often uncostly and unmonetized, pleasures and values that make life worth living. Eyres is the author of the poetry collection Hotel Eliseo, Plato’s “The Republic”: A Beginner’s Guide, and several books on wine. You can find him online @sloweyres.

Horace and the Ages of Excess

by Harry Eyres

While researching Horace and Me, my book on the Roman poet (and a few other things besides), I was astonished time and again by the uncanny prescience of this ancient and some might think antiquated poet; by how pertinent so many of his words remain, two thousand years after they were written. Perhaps it was something like the experience an archaeologist has, pushing a spade into long-dormant earth and coming up with a perfect glittering coin or piece of jewelry: how can this thing still be shining so bright after so long?

Horace wanted his poems to be useful as well as sweet. He offers not just beautiful images and rhythms, but a philosophy of living well. It is a poet’s philosophy, that is to say it is thoroughly human, grounded in experience, not theory, and accepting of inconsistency, of the fact that the noblest philosophy can be undone by a bad cold.

Some of the words that seemed truest came in one of his verse letters, or Epistles, written to a friend called Bullatius. They concerned the mania for traveling which afflicted wealthy Romans in the time of Augustus almost as much as it afflicts us. Horace begins with a list of famous islands and beauty spots which his friend has just visited on his trip to the eastern Aegean. Are Samos, Chios and Lesbos all they are cracked up to be, and how do they compare with the familiar sights of Rome?

Horace himself prefers a desolate place called Lebedus, quite the opposite of a tourist trap: a back-of-beyond hole with, as it were, no wifi or cell-phone coverage, where he would like to live completely secluded from the world.

Traveling, he goes on to say, doesn’t really get you anywhere; “if it’s really reason and philosophy, not a splendid sea-view, which remove anxiety and restore the mind to health, then those who cross oceans only change the climate, not their state of mind.”

I like sea views myself (Horace obviously did too), and I treasure my memories of visiting Greek islands and beauty spots, but I can also recognize the deeper truth that however far you travel, you cannot get away from that chief source of all your joys and sorrows: yourself.

The very end of Horace’s epistle to Bullatius is possibly even more pertinent to our times. My loose modern version goes like this: “a sort of busy idleness wears us out;/We think the best way to live is to buy a yacht or an SUV;/ Everything you need is here, in Pitsville, if your mind is sane.”

Horace wrote his Odes at the beginning of the Imperial age in Rome, a time of relative peace (the terrible Civil Wars, in which Horace fought on the losing side, were over, the main foreign enemies defeated) and growing affluence. But Horace saw that growing wealth did not necessarily bring inner peace or environmental balance. He railed against the excesses of plutocrats, the pollution and noise of Rome, the ridiculous over-refinements of Roman gastronomy. These are all things we can relate to in our own age of excess.

Horace’s most famous phrase is still, I think, the deepest and the best. “Carpe diem,” in my reading, does not mean seize the day, with violence and a kind of desperation, but pluck it and taste it, like a grape, a grape which will turn into wine, that wonderful liquid which, like poetry, restores and revives.

Source:

http://www.fsgworkinprogress.com/2013/06/horace-and-the-ages-of-excess/

Ram Dass

Ram Dass  Dalai Lama

Dalai Lama