Documentary from 1997

©1997 Troivision Co., Ltd/Warabe No Mori Co., Ltd.

kobayashi dldg, 4-7 Yotsuya Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo Japan

The Japanese sword is the soul of the Samurai. The crafting of this work

of art - which embodies beauty, strength and tradition - has been

shrouded in secrecy for more than thousand years.

Because of the highly advanced techniques and numerous years of

dedicated effort required in crafting Japanese swords, the skill has

always been a closely kept and jealously guarded secret.

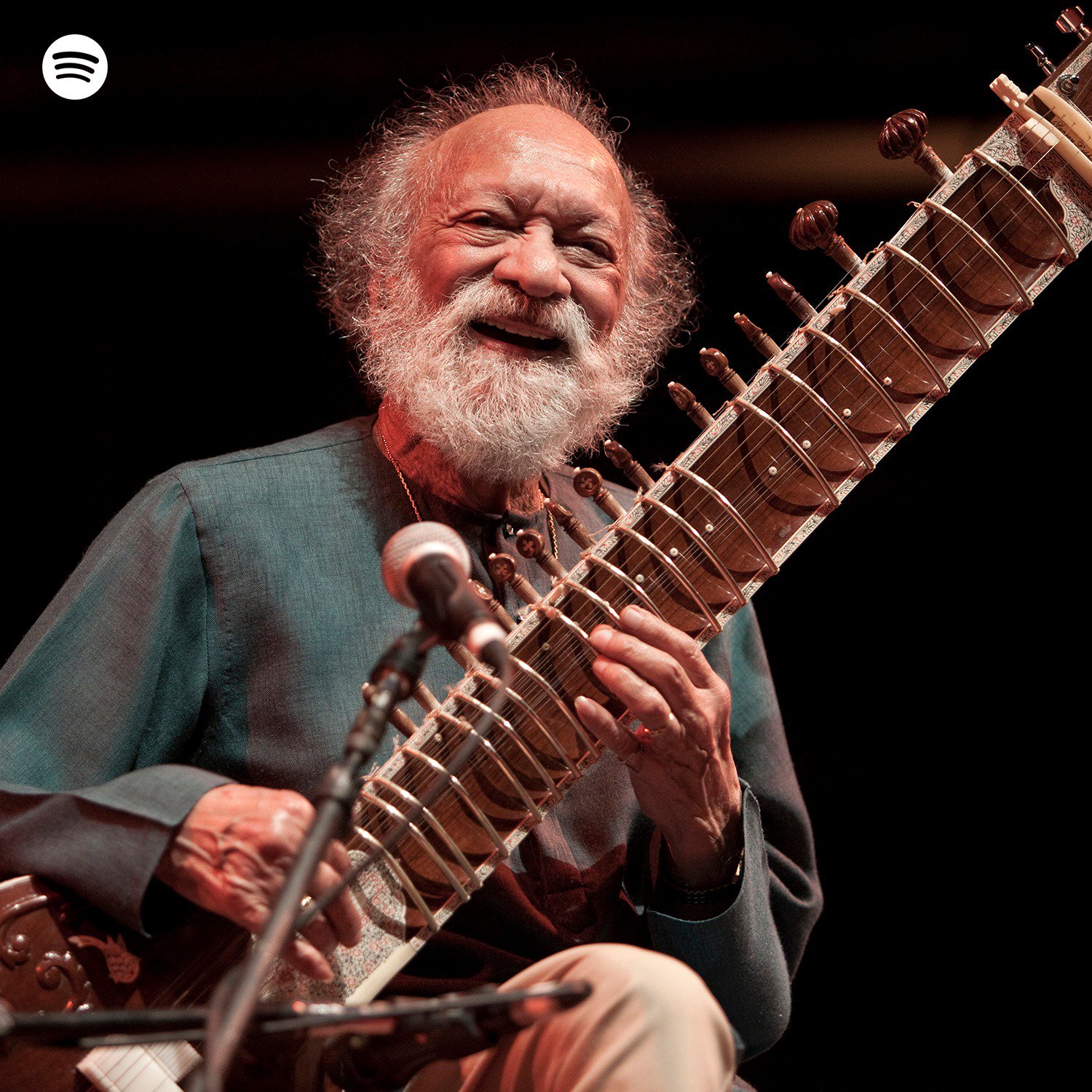

Yohindo Yoshihara is a consummate Japanese swordsmith and a very high

regarded Mukansa craftman in Japan.

He is also the best-known Japanes

swordsmith outside of Japan.

His masterpieces have been purchased for exhibit by the Metropolitan

Museum of art in New York City and the Museum of fine Arts in Boston.

He

has numerous fans worldwide, including His Royal highness, king Gustav

of Sweden.

This video has been produced to appeal to all aficionados of Japanese

sword around the world and is a treasure trove of sercrets to Yohindo

Yoshihara's truly outstanding Japanese sword craftsmanship.

Yoshindo Yoshihara

Swordsmith

Yoshindo

Yoshihara is a Japanese swordsmith based in Tokyo. His family have made

swords for ten generations, and he himself learned the art from his

grandfather, Yoshihara Kuniie.

Yoshindo himself gained his licence as a

smith in 1965.

Yoshihara uses traditional techniques in his work, and uses tamahagane

steel.

Wikipedia

Deadly weapons forged as art

There's a gory history to every Japanese sword — even those being made today

Apr 27, 2008

The slow, rhythmic thrust of a piston covered in

tanuki

(raccoon dog) skin blasted air from box bellows onto the searing-hot

charcoal. A casual glance at his forge was, however, all that Yoshindo

Yoshihara needed to know the fire’s exact temperature.

His sharp

eyes behind his glasses may have been intent on that vital blaze, but

they also appeared completely relaxed as this rather small man with a

goatee beard brought his decades of experience to bear — working, it

seemed, completely absorbed in the moment. Then suddenly, in the blink

of an eye, he yanked the red-hot length of metal off the bed of fire

with a pair of long-handled pliers and across onto an anvil.

No sooner had Yoshihara done this than the two young men

beside him began to bring down their hammers alternately on the metal,

filling the downtown Tokyo workshop with the clanging and ringing of

their blows. Sparks flew in all directions as this master swordsmith

gripped the pliers unflinchingly, staring fixedly at the red-hot metal.

The

days when samurai ruled Japan with an iron fist may have ended some 150

years ago, but in this smoke-blackened smithy their presence lingers

on, as it does in many aspects of Japan’s culture, from the traditional

noh and kabuki theatrical forms in which they so often feature to the

rigidly hierarchical structure of its companies, in which underlings

still often refer to the boss between themselves as the “top samurai.”

Indeed,

some people will tell you that the reason cars are now driven on the

left-hand side of the road is because the samurai, who wore their swords

on their left hips, would walk on the left so the tips of their long

scabbards would not touch. Should that by chance occur, it would be

considered the height of insolence and reason enough to fight a duel to a

chillingly bloody conclusion.

Not that the samurai — the only one

of the four divisions of feudal Japanese society (whose other classes

were farmers, artisans and merchants) allowed to wear swords in public —

would look for any excuse to draw their swords in the way swashbuckling

movies like “The Last Samurai” might suggest. In fact, to members of

that fabled warrior class, the cold, hard steel of their swords

transcended mere lethal weaponry to symbolize no less than their very

souls.

“If the sword was just a tool, why would

tokkotai

(suicide-mission) pilots during the Pacific War have one stowed in the

cockpit of their planes that they aimed to slam into oblivion against an

enemy ship?” says Yoshihara, who is one of Japan’s top swordsmiths.

Indeed,

there are countless fables and legends extolling the power and mystique

of the Japanese sword, and its role in Japanese history, with one named

Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi even mentioned in the eighth-century “Kojiki

(Records of Ancient Matters),” Japan’s oldest surviving historical

record. There, it is identified as one of the three Imperial regalia,

along with a jewel and a mirror.

In 1185, it is said that the 6-year-old

Emperor Antoku drowned clutching it in his arms during the defeat of

his Taira clan at the great sea Battle of Dannoura off present-day

Yamaguchi Prefecture, rather than have it captured by the enemy Genji

clan.

For Yoshikazu’s part — not to be outdone by his dad —

martial-arts movie star Jackie Chan popped in recently to purchase one

of his creations.

Sword stores sell both new swords and old swords

that are hundreds of years old. At the Sokendo store in Harajuku,

Tokyo, the cheapest sword costs about ¥300,000 and the average price is

¥1 million.

At 41, Yoshikazu has many years ahead of him to carry

on the Yoshihara style of sword-making, and the future will be even more

secure if his son in turn follows in his father’s footsteps.

Me, though, I was keen to know if Yoshihara thinks this ancient art form would still be around 100 years from now.

“If

you count one generation as lasting 25 years, 100 years would be four

generations,” Yoshihara said. “Judging from the current state of

sword-making in Japan, I think there will still be swordsmiths around a

century from now. How many, though, I don’t know.”

Not that the sprightly 64-year-old Yoshihara is ready to pass on the torch to the next generation just yet.

“With

every sword I make,” he said, smiling, “I try to improve on my last

one. But I still haven’t made one that I am 100 percent satisfied with. I

know that will never happen, though — even to my dying day.”

First Look

First Look

Epitome of Wisdom

Epitome of Wisdom